Miscela Strategica – Durante Eurosatory 2016 abbiamo intervistato Robert Limmergård, segretario generale di SOFF, l’associazione che raggruppa le aziende svedesi operanti nel settore sicurezza e difesa

[one_half]

Mr. Limmergård, why is Eurosatory important for your countries companies? What outcomes do you expect from it?

Eurosatory is an international exhibition and it brings together not only – even if mainly – European industries, but also international companies. We have learned this is a really good exhibition for B2B; in the past it was an opportunity to meet governmental organisation, but for most of our companies it is more about meeting other businesses.

As a federation, do you have specific strategies to support your companies’ competitiveness?

To some extent, we do. We work on trying to influence the access to market through working at regulation, but also by networking and by expanding knowledge.

First, regulation, which is pro-market, is something of great interest; we are never involved in business, so we work pro-market rather than pro-business.

Second, in doing that, we ensure our member companies are well informed about foreign companies, markets and technologies they are interested in; awareness-building is a core issue for us, especially for what concerns European programmes, researches and that kind of things. Although this information is of great importance, it is very hard for smaller companies to understand what is of their interest. We, as federation, are to some extent nearer to Brussels, and therefore we could help our associates in understanding which programmes could be interesting for them.

In order to carry out our project, we had the chance to interview companies coming from Northern and Eastern Europe. A number of them told us one of their major problem is the lack of situational awareness: industries coming from Western Europe usually do not know who they are and what they do. As a consequence, they found quite difficult to cooperate with them. In the meanwhile, Eastern and Northern companies are growing and advancing. In your opinion, this trend goes towards threatening older Western companies, or rather, are they struggling for integrating?

Taking the example of Nordic cooperation, there have been many trials but few success in terms of cooperation – especially when it comes to procurement or harmonisation of requirements. We have failed even on a regional basis, despite expectations – as the group was formed by four countries only, we thought it should have proven successful.

What has not failed is the business, because companies work more and more closer: nowadays there is more interaction and more joint business amongst Nordic companies than five years ago. The current trend is that companies from the South are integrating themselves; this is a trend we are seeing in the wider European area, but efforts seems to be focused on the Southern region. The problem is, how do you actually know who to play with considering the high number of corporations. Reaching out to companies is something like what we have here: we have 25 Swedish companies exhibiting here, 15 of them are trying to use the exhibition to find partners, to learn more about other companies; the problem is that it takes time, and it is complicated, especially because sometimes is hard to understand the other companies’ technological level and, as a consequence, to understand what they are looking for. Doing this kind of mapping, you could also participate in defence industry seminars organised in some countries. There are very positive use of businesses tenders, and – even more interesting – the opportunity to listen to other companies and defence ministers. But this is highly demanding and costly in terms of time – but also in financial terms.

You have just confirmed what we have discovered while carrying on our project. If we want to build a real industrial base at the EU level, probably the bottom-up approach will be the best one, as industry are starting to cooperate more between them even though a proper EU industrial base does not exist yet. Do you think the creation of an effective EU industrial base will be possible? In fact a legal framework exists already, but some of its tools are not much used – i.e. the certification system and the registration system – despite they will increase the knowledge about who does what in Europe and enhance cooperation…

The problem with these examples has always been that companies searched win-win strategies so far. The European directives were very important and it is too early to evaluate them. It is usually estimated that EU directives take 6 to 8 years before being implemented. Having said that, the intra-EU trade represents a really small percentage: if you go into details it represents 6%, which is nothing compared with the overall defence market.

Yes, it might be that businesses themselves will drive industry’s efficiency and consolidation, but it is not enough, as you need both sides. When the six nations voted for the Farnborough (LoI)-agreement – which I think was very important because since then they started to think about what industries need to work together about – they have tried to identify the most important areas for cooperation and to translate them at the political and administrative level in order to make industries to work better. A lot have been achieved in many fields, but still when it comes to security of supply, export control regimes, technical information, military requirements and R&D, in all these areas we have taken small steps, and not big steps – which means that the steps companies take contribute for big steps. In addition, we also have a lot of new actors, new companies that you can see, not only from the civil sector, but also from the international sector, who are establishing themselves within the European landscape. They can be South Korean, they can be Chinese and that kind of competitiveness – which let them increase their influence – will make impossible for common companies not to act on. So I think the trend about civil companies and civil technology as well as for competition will shape the European landscape for the years to come.

[/one_half]

[one_half_last]

Perché Eurosatory è importante per le aziende svedesi? Cosa vi aspettate dalla partecipazione?

Eurosatory è un salone internazionale, e il vantaggio di parteciparvi è proprio questo. L’evento mette insieme non solo – anche se prevalentemente – le aziende europee, ma anche le realtà internazionali. Abbiamo imparato che è un’ottima occasione per il B2B. In passato rappresentava un’occasione per incontrare le organizzazioni governative, ma per le nostre associate è il luogo per conoscere altre persone e nuovi business.

Come federazione, SOFF mette in pratica delle strategie specifiche per supportare la competitività delle aziende che ne fanno parte?

Per certi versi lo facciamo. Lavoriamo per cercare di influenzare l’accesso al mercato guardando alla regolamentazione, ma anche al networking e alla conoscenza. La regolamentazione, che è orientata al mercato, è di interesse primario. SOFF non è mai coinvolta negli affari, e questo è il motivo per cui la nostra attività è orientata verso il mercato piuttosto che verso gli affari stessi. Nel fare questo ci assicuriamo che le nostre federate siano ben informate sulle aziende, i mercati e le tecnologie di loro interesse. L’informazione è molto importante per noi, specialmente in relazione a programmi, ricerche e, in generale, a tutto ciò che avviene a livello europeo. Nonostante queste informazioni siano di fondamentale importanza, le aziende più piccole faticano a capire cosa sia di loro interesse e ad inserirsi in quello specifico settore. Noi, essendo una federazione, siamo per certi aspetti più vicini a Bruxelles di quanto non lo siano loro, e quindi possiamo aiutare i nostri associati a comprendere meglio quali programmi siano potenzialmente di loro interesse.

Come ricerca sul campo per il nostro progetto, abbiamo intervistato diverse aziende provenienti dal Nord e dall’Est Europa. Per molte di queste, stando a ciò che ci hanno detto, uno dei principali problemi è la scarsa (talvolta nulla) conoscenza della situazione: le aziende provenienti dall’Europa occidentale spesso non conoscono chi sono e di cosa si occupano. Di conseguenza per loro è abbastanza difficile trovare delle forme di collaborazione. Nel frattempo, le aziende di Nord ed Est Europa crescono e avanzano. Secondo lei, questa tendenza rappresenta una sfida alle industrie occidentali, o piuttosto un tentativo di integrazione?

Prendendo l’esempio della Nordic cooperation, ci sono stati diversi tentativi ma pochi successi in tema di cooperazione – soprattutto per quella relativa a procurement o armonizzazione dei requisiti. Abbiamo fallito pure su base nordica nonostante le aspettative: visto che il gruppo era composto da soli quattro membri, si prevedevano buone possibilità di successo.

Quello che non è fallito sono gli affari, perché il livello di cooperazione tra le aziende è aumentato: oggi ci sono più interazioni e attività economiche congiunte tra aziende del Nord Europa di quanto non avvenisse cinque anni fa.

La tendenza odierna è che le aziende del Sud si stanno integrando; la tendenza, in realtà, è pan-europea, ma sembra che gli sforzi maggiori si stiano concentrando nell’Europa meridionale. Il problema è comprendere con chi si vogliono fare affari in presenza di un numero così elevato di aziende. Le nostre federate presenti qui cercano di fare proprio questo. Dei 25 espositori svedesi, 15 stanno usando Eurosatory per cercare nuovi partner e conoscere di più delle altre aziende. Il problema è che tale ricerca richiede tempo ed è complicata, perché talvolta è difficile comprendere il livello tecnologico su cui le altre aziende si attestano e, di conseguenza, anche cosa cercano. Mentre si fa una simile mappatura si può anche partecipare ai seminari che qualche Paese organizza sull’industria della difesa. Ci sono buoni modi per usare le offerte di affari e ascoltare – cosa forse ancor più interessante – le opinioni e le necessità delle altre aziende e dei Ministeri della difesa. Ma questo è molto impegnativo e dispendioso in termini di tempo – ma anche economici.

Ha appena confermato quello di cui ci siamo resi conto effettuando le ricerche per il nostro progetto. Se vogliamo costruire una vera base industriale a livello europeo, probabilmente l’approccio bottom-up sarebbe il migliore, visto che le aziende cooperano sempre di più anche in assenza di una base industriale europea propriamente detta. Crede che la creazione di questa base sia davvero possibile? Nei fatti un quadro legislativo esiste già, ma alcuni dei suoi strumenti, sebbene potenzialmente utili a conoscere chi fa cosa in Europa e a rilanciare la cooperazione, non sono largamente utilizzati. Penso in particolare al sistema di certificazione e alle registrazioni….

Il problema con questi esempi è sempre stato che le aziende, in fondo, cercano delle strategie win-win. Quando si guarda al mercato europeo in sé….le direttive europee sono molto importanti, ma è ancora presto per valutarle. Abitualmente si stima che le direttive europee impieghino tra i sei e gli otto anni prima di essere implementate. Ciò detto, bisogna considerare che il mercato intraeuropeo rappresenta appena il 6% del totale, percentuale ridottissima se si considera il mercato nella sua interezza. Sì, è possibile che siano le stesse aziende a guidare l’efficientamento e il consolidamento del comparto, ma questo non è abbastanza, perché sono necessarie entrambe le parti.

Quando i sei Paesi proponenti hanno votato l’accordo (Lettera di Intenti) di Farnborough – che a mio parere è stato molto importante, perché da quel momento questi Stati hanno iniziato a pensare a quali necessità bisognasse soddisfare perché le industrie potessero lavorare insieme – hanno cercato di identificare le aree più rilevanti per la cooperazione e di tradurle a livello politico e amministrativo perché le aziende potessero lavorare meglio. A tal proposito molto è stato raggiunto, ma quando si parla di sicurezza degli approvvigionamenti, controllo delle esportazioni, informazioni tecniche, requisiti militari e R&S, sono stati fatti solo piccoli passi, ma non quelli grandi. In più, siamo di fronte a un elevato numero di nuovi attori, nuove aziende arrivate dal settore civile o dal mercato internazionale, che stanno cercando il loro posto nel panorama europeo. Queste possono essere sudcoreane o cinesi, e le industrie già presenti non possono far altro che cercare di agire ai loro livelli di competitività – che poi sono quelli che consentono loro di affermarsi sul mercato europeo.

Quindi penso che le tendenze provenienti dal settore civile (in termini di aziende e di tecnologie), insieme alla competitività, saranno i fattori che influenzeranno il panorama europeo per i prossimi anni.

[/one_half_last]

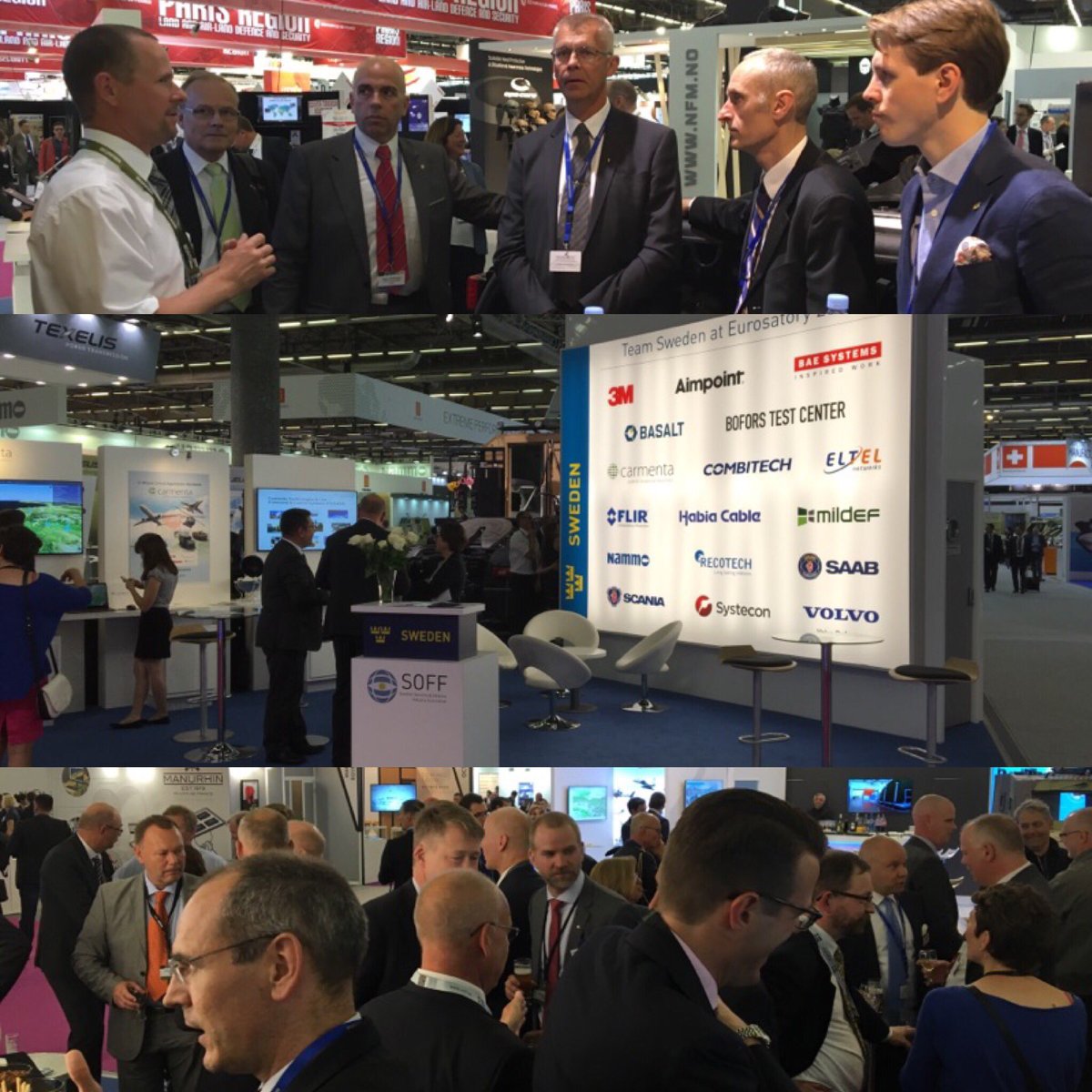

Fig. 1 – Il national pavillion svedese a Eurosatory. Credits: @SOFF_SE

[one_half]

Who your competitors are within and outside Europe?

It depends very much on the kind of technology you refer to. If I ask to the companies here [at the Swedish pavilion] they will probably pinpoint to Swiss companies and Canadian companies; but if we ask that company [pointing towards a specific exhibitor] they will say Germany and France. So it depends on technology and products.

So it really depends on the business…

To be more accurate on the technology the industry is specialised in. What is also important is the security framework, because, when it comes to bigger platforms – as Gripen and submarines, in the Swedish case – the business still depends on relations between governments. Because when you have a platform, like submarines, for fifty years, a lot of trust needs to be built around that to be able to operate the system, and so on and so forth. In this regard the relation is not only about businesses, but also within governments.

Focusing at the EU level, in 2016 defence budgets are expected to raise. Do this influence the activities of SOFF’s associates?

I would say that when it comes to budgets in Europe, my view is that we see a third of the EU countries are actually increasing their budgets, a third of it is in, real money, still decreasing them, while the last third is more or less at the same level, if we take into account inflation rates and other costs. What we see is rather focus within the budgets: usually the increase goes for personnel or to sustain/upgrade existing programs, while countries spend less on new products. If you have to compete, for example, with the US, or India or China this happens with regards to new technologies and innovations. In this regards, China and the US spend a lot more on R&D and innovation. So, the whole issue is not simply about defence budgets as such, but rather on the way of speding, how much you spend on R&D, on the purchase of new materials, which are definitely more important. Our biggest worry is that Europe is fragmented and it is spending less. My companies, as anyone else in Europe, are looking at exporting to other countries. But we cannot sustain our competitiveness relying on exports only. We need to develop and fund ourselves, and to do that we need an efficient European market.

Geopolitics is a core issue for Il Caffè Geopolitico. To what extent geopolitics impacts your country’s business opportunities – especially considering the geographical position Sweden has?

Swedish armed forces have been focusing on international operations in the past 10-15 years, but they have now shifted to the regional area. To be more specific, everything is played around anti- access/area denial in the Baltic sea, to be able to have access – or deny access – to this specific area, in water, underwater, in the air. This is probably the capability on which the Swedish armed forces are spending more, as they will need to upgrade almost all the systems they have. What we see is that, for example, Iskander or S400 systems – the Russian systems – are so technically advanced that we are actually lacking capabilities to deal with them. Therefore we will focus our capability building on anti-access/area denial technologies.

You partially anticipated the following question, which was about future scenarios and capabilities. How do you see your companies in the future?

There is one, big worry: since the government is spending less on R&D, and a growing part of R&D is financed through export, companies themselves finance more on R&D. In doing that there is a technology transfer to other countries, which could become bigger markets.

For my member companies, 60 to 70 % is exports. So when they finance the R&D on their own – so the government does not have any stake nor it has royalties – we do not own the IPR. So today is much easier for companies being globalised, to move their competences, to vary the market or the technologies.

And also, in the EU political domain, they have also started to compare business conditions among member states. This is what happens with the so-called license shopping: if one country has a more favourable system and another actually has a discriminating system – for example when it comes to export control –, this really influence the way companies do their business, and in the end where they do their R&D. And R&D is the beginning of what see here today: everything here is built on success obtained taking innovations to the market, and if we are not able to compete, it does not really matter which products will be used.

[/one_half]

[one_half_last]

Chi sono i vostri competitor in Europa e fuori?

Dipende molto dalla tecnologia alla quale si fa riferimento. Se chiedessimo alle aziende che si trovano qui [al padiglione nazionale svedese, ndr] probabilmente indicherebbero aziende svizzere o canadesi. Se chiedessimo all’azienda che si trova laggiù [indicandone una specifica, ndr], probabilmente risponderebbe Francia e Germania. Insomma, è diverso in relazione alle tecnologie e ai prodotti.

Quindi in realtà dipende dal settore di attività…

Più precisamente dalla tecnologia in cui l’azienda è specializzata. Altro elemento importante è il quadro di sicurezza, perché quando si producono grandi piattaforme – come i Gripen e i sottomarini, nel caso svedese – gli affari dipendono dalle relazioni tra governi. Quando utilizzi un sistema d’arma, diciamo un sottomarino, per cinquant’anni, è necessario un vincolo fiduciario con chi opera il sistema e simili. Per questo aspetto, dunque, la relazione non è solo questione di affari, ma anche di relazioni tra governi.

A livello europeo, i budget per la difesa sono previsti in aumento per il 2016. Questo influenza le attività delle vostre federate?

A mio parere, quando si parla di budget in Europa vediamo che un terzo dei Paesi lo sta effettivamente aumentando, un terzo (in termini di valuta reale) lo sta ancora diminuendo, e un terzo lo sta mantenendo più o meno invariato – se consideriamo inflazione e altri costi.

Quello che più importa, in realtà, sono le allocazioni del budget: abitualmente gli aumenti sono destinati al personale o al sostegno/aggiornamento dei programmi esistenti, mentre i Paesi spendono meno per i nuovi prodotti.

Se devi competere, per esempio, con gli Stati Uniti, la Cina o l’India, lo fai relativamente a nuove tecnologie e innovazione. E a tal proposito, Cina e Stati Uniti spendono molto di più in R&S e innovazione.

Quindi non sono i budget per la difesa in sé, ma piuttosto gli stanziamenti per R&S e per l’acquisto di nuovi materiali a essere davvero importanti.

La nostra paura più grande è la frammentazione dell’Europa, in cui si spende meno nella difesa. Le nostre associate, come tutte le aziende europee, cercando di esportare. Ma non possiamo sostenere la nostra competitività esclusivamente attraverso le esportazioni. Dobbiamo svilupparci e finanziarci, e perché ciò avvenga è necessario un mercato europeo efficiente.

La geopolitica è un tema fondamentale per la nostra rivista. In che misura questa influenza le opportunità di affari delle vostre federate – soprattutto considerando la posizione geografica della Svezia?

Per gli ultimi 10-15 anni le Forze armate svedesi si sono concentrate sulle operazioni internazionali, ma adesso sono tornate a privilegiare l’impegno regionale. Più in dettaglio, tutto si gioca intorno all’anti-access/area denial nel mar Baltico, finalizzato ad avere accesso a quest’area specifica, o a inibirlo, in acqua, sott’acqua, in aria. Probabilmente questa è la capacità su cui le Forze armate svedesi stanno spendendo di più, visto che necessitano di aggiornare quasi tutti i sistemi in dotazione. Ci rendiamo conto che, per esempio, gli Iskander e gli S400 – i sistemi russi – sono talmente avanzati rispetto ai nostri che attualmente non possediamo capacità idonee a contrastarli. E questa è la ragione per cui ci concentreremo sulla costruzione di tecnologie per l’anti-access/area denial.

Ha parzialmente anticipato la mia prossima domanda, che riguarda gli scenari future e le capacità. Cosa vede nel futuro delle federate di SOFF?

C’è un’unica, grande paura: visto che il Governo ha diminuito gli investimenti in R&S, e una crescente parte di questa viene finanziata attraverso le esportazioni, sono le stesse aziende a dover investire in R&S. Nel fare questo c’è un trasferimento di tecnologia agli altri Paesi, che possono diventare mercati più grandi.

Per le federate SOFF il 60-70% delle vendite avviene all’estero. Quindi quando finanziano autonomamente la loro R&S – e quindi senza che il Governo possieda quote o paghi royalties – non possiedono i relativi brevetti.

Dunque oggi è più semplice che le aziende diventino globalizzate, traferiscano le loro competenze, cambino i mercati di riferimento o le loro tecnologie.

E in aggiunta, nell’ambito della politica UE, si è anche iniziato a comparare le condizioni di business fra i vari Paesi. Questo è ciò che avviene con il cosiddetto mercato delle licenze: se un Paese ha un sistema più favorevole e un altro presenta un sistema più discriminante – ad esempio relativamente al controllo delle esportazioni –, questo influenza fortemente il modo in cui le aziende nazionali fanno affari, e dunque come finanziano la propria R&S. E la R&S è alla base di quello che vediamo qui oggi, costruito sui successi ottenuti introducendo innovazioni sul mercato. Ma se non saremo in grado di competere, poco importerà quali tecnologie o prodotti saranno utilizzati.

[/one_half_last]

The interview ends here. We warmly thank Robert Limmergård and SOFF for the kind cooperation

Giulia Tilenni

[box type=”shadow” align=”” class=”” width=””]

SOFF , the Swedish Security and Defence Industy Association, provides support to its 65 members – mainly SMEs – trying to set the best possible preconditions for their business. To this end SOFF represents Swedish security and defence industries at ASD (AeroSpace and Defence Industries Association of Europe), NIAG/PfP (NATO Industrial Advisory Group/Partnership for Peace) and are the appointed Swedish National Defence Industry Association (NDIA) towards the EU (European Defence Agency, EU Commission) and in the Nordic context (NORDEFCO).

SOFF, l’associazione delle industrie svedesi operanti nei settori difesa e sicurezza, supporta le 65 federate – principalmente piccole e medie imprese – cercando di creare le migliori precondizioni possibili per il loro business. A tale scopo SOFF rappresenta le aziende di settore presso ASD (AeroSpace and Defence Industries Association of Europe), NIAG/PfP (NATO Industrial Advisory Group/Partnership for Peace) e rappresenta l’associazione svedese di categoria presso le istituzioni europee (EDA, Commissione) e nel contesto nordico (NORDEFCO).

Questa intervista è parte dello Speciale Eurosatory 2016. Vi suggeriamo di consultarlo per approfondire i temi del salone e leggere le interviste già pubblicate. [/box]