Miscela Strategica – Durante Eurosatory abbiamo avuto il piacere di parlare con Henrik Vassallo, capo dell’unità Francia e Benelux della svedese SAAB. Anche con lui ci siamo confrontati sui temi a noi cari, e in particolare sulla difesa europea e le industrie del settore

[one_half]Mr. Vassallo, do you believe a cohesive European industrial base can be pursued for real? Would it suit your strategies?

My former job was head of the EU affairs and NATO for SAAB and we have of course been highly involved in trying to ensure that the defence procurement directives will be put in place in such a way that it allows a fair and open competition.

The European industrial base spreads across Europe, but let’s say six States have most of the industrial base – namely France, Sweden, Germany, UK, Italy and Spain. EU directives should be developed in a way that ensures a cross border, fair and open competition amongst these producing member states – LoI (Letters of Intent) countries –, which are also the procuring member states. To sum up, every time they procure this should happen through open competition, allowing producing/procuring countries to bid contracts everywhere across Europe.

As fieldwork for our analytic and investigative project we had interviews with industries coming from Eastern and Northern European countries. A number of them told us they had several difficulties in getting into the EU defence market. Amongst them the fact that bigger companies wanted to drag them within their industry rather than integrate them in the EU market. How do you see this trend? Do you perceive these newcomers would represent a threat for Western industries, or are they effectively trying to integrate themselves within the EU defence market?

As I previously said, a fair and open competition is what we are looking for, as this will be the premise for an EU industrial base. The EDTIB is not a fixed thing: at a first stage we had local markets procuring from local contractors; later on, as a development of this existing system, the idea of a common industrial base has been developed and enhanced.

Now that we have this framework in place – these EU defence procurement directives – we hope for us and for smaller competitors (across the whole Europe, not only in Northern Europe or in the Baltics) this should be implemented for real, establishing a proper European industrial base. This should happen in a direction which allows them to enter in the market and become part of it: not only to let them cooperate for what concerns mergers and acquisitions, but to make them able to take their place within the market.

How do you see competition within todays EU market? As you said, you are struggling for it; but todays defence market does work as a liberal one? For example, if you think to France and UK, the majority of the companies belonging to the defence market are – at least in part – public companies; this means that maybe competitiveness does not represent a core issues for them.

A public company is of course working on the market. If you refer to private companies or state owned companies, they play a fundamental role in defining how the market looks like. There is no illusion from the legislator that these companies could work like the ones operating in the normal, civilian market. Defence is different, but of course the extent of being different has, in our view, not to be taken too far. Defence is different but should also be able, at least for what concerns some procurement aspects – i.e. how you pursue procurement in general –, to work like the civilian market. Of course certain cases, certain programs, have to be handled in a more national, sensitive way, but the bulk of the procurement should be open to competition.

I would say that defence, step by step, is getting closer to the functioning of the traditional civilian market.

In 2016 defence spending are rising again in Europe. Do this affect SAAB work?

Of course when we look at markets to penetrate in and to work for, we are influenced by macroeconomic trends as the one you mentioned – defence budgets going up or going down.

On the other hand, we are a 2.5 billion euro company, so if we decide to enter in a market we of course do not monopolize that market. And this goes back again to what I said before: if there is the chance for competition, if we feel we have the chance to be treated fairly and to compete in the fields and capabilities we feel strong in, we enter in that market even if trends are negative. And we have often tried to do that in collaboration with the incumbent actors; for example here in France we are open for partnership – as recalled by our motto here at Eurosatory, «bringing ideas together». So we are partnering with other companies to put something on the market which could attract customers not only within the European market, but also for foreign markets.[/one_half]

[one_half_last] Signor Vassallo, crede sia realmente possibile creare una base industriale europea coesa? Questo andrebbe d’accordo con le vostre strategie?

Prima di ricoprire il mio attuale incarico ero capo della sezione affari europei e NATO dell’azienda, ed eravamo particolarmente coinvolti dal tentativo di assicurare che l’implementazione delle direttive europee sul procurement portasse a una competizione aperta ed equa.

La base industriale europea si diffonde in tutta Europa, ma sono sei i Paesi ad avere le basi industriali più avanzate – Francia, Svezia, Germania, Gran Bretagna, Italia e Spagna. Le direttive europee, dunque, dovrebbero svilupparsi in modo tale da incentivare una cooperazione chiara, aperta e transnazionale tra questi Paesi – i firmatari delle LoI (Letters of Intent) –, che sono quelli più attivi nel procurement. In sintesi, qualsiasi approvvigionamento da parte di questi Stati dovrebbe avvenire in regime di competizione aperta ed equa, cosicché Paesi produttori e compratori possano stipulare contratti ovunque in Europa.

Il lavoro sul campo che abbiamo condotto per il nostro progetto analitico/investigativo ci ha portato a parlare con aziende provenienti dall’Est e dal Nord Europa. Molte di loro hanno palesato difficoltà di inserimento del mercato europeo della difesa. Tra queste il fatto che le aziende più grandi propendono per cooptarle piuttosto che per integrarle nel mercato europeo. Cosa può dirci di questo trend? Crede che queste nuove aziende potranno sfidare i Paesi occidentali, o i loro sforzi sono effettivamente finalizzati all’integrazione nel mercato della difesa europeo?

Come ho già detto, noi miriamo a una competizione aperta ed equa, perché è questa la premessa per una base industriale europea. La EDTIB [European Defence Technological and Industrial Base – nda] non è granitica: in un primo momento c’erano i mercati locali che si approvvigionavano presso produttori locali; in seguito, come sviluppo del sistema esistente, è nata e si è sviluppata l’idea di una base industriale comune.

Adesso che il framework esiste – le due direttive europee sul procurement della difesa – speriamo per noi, e anche per i competitor più piccoli (di tutta Europa, non solo del Nord e del Baltico), che questo venga realmente implementato, creando una reale base industriale europea. Questo dovrebbe avvenire in modo da consentire il loro ingresso e la loro integrazione nel mercato: non solo dare la possibilità di cooperare in termini di fusioni e acquisizioni, ma consentendo loro di trovare un posizione nel mercato.

Come vede la competizione nel mercato europeo attuale? Come ha affermato Lei stesso, state lottando per averla; ma ad oggi il mercato funziona in modo liberale? Per esempio, pensando a Francia e Gran Bretagna, la maggior parte delle industrie della difesa sono – almeno in parte – partecipate dallo Stato; questo significa che la competizione per loro non è una questione centrale.

Anche quando pubblica, un’azienda deve operare sul mercato. Se il riferimento è alle compagnie private o a quelle statali, queste hanno un ruolo fondamentale nella definizione del mercato stesso. Il legislatore non si illude che tali aziende possano agire come quelle che operano nel settore civile. La difesa è differente, ma di certo l’entità della differenza, a nostro parere, non va portata oltre un certo limite. La difesa è differente, ma deve essere capace, almeno per ciò che riguarda alcuni aspetti il procurement – ad esempio come questo è gestito in generale – di funzionare analogamente al mercato civile. Sicuramente in certi casi, per certi programmi, deve essere gestita in un modo più nazionale e sensibile, ma lo zoccolo duro del procurement deve essere aperto alla competizione.

Direi che la difesa, pian piano, si sta avvicinando al funzionamento del mercato civile.

Nel 2016 le spese europee per la difesa stanno nuovamente salendo. Questo ha implicazioni per il lavoro della vostra azienda?

Quando guardiamo ai mercati su cui entrare e in cui lavorare, siamo influenzati da trend macroeconomici come quello appena richiamato – la variazione dei budget per la difesa.

D’altro canto, però, siamo un’azienda da 2,5 miliardi di euro, quindi se decidiamo di entrare su un mercato non è di certo per monopolizzarlo. E questo si ricollega a ciò che dicevo prima: se c’è una possibilità di competere e di essere trattati in modo imparziale, competendo nei settori e per le capacità in cui ci sentiamo forti, entriamo nel mercato anche se i suoi trend sono negativi. E spesso abbiamo cercato di farlo in collaborazione con nuovi attori; per esempio siamo aperti a nuove partnership qui in Francia – come richiamato qui a Eurosatory dal nostro motto, «mettendo le idee insieme». Quindi stiamo creando delle partnership con altre aziende per immettere sul mercato qualcosa che possa attrarre non solo i compratori del mercato europeo, ma anche i mercati stranieri.[/one_half_last]

[one_half]How much and to what extent geopolitics affects SAAB’s business?

If you mean conflicts, for example, of course they have an influence. When there is a conflict you have to work on what needs to be used, and this works for all industries.

If you refer to geopolitics in terms of finances, economics and procurement budgets of course these are important aspects for us to follow and monitor, to ensure we are allocating our scarce resources in the right marketplace and penetrating market which are relevant for us.

What about offsets? Offsets are growingly important, becoming more common than in the past…

Offsets are a specific issue. As I am sure you understood when you did this work [the analytic and investigative project we had the chance to present], part of the reform of the defence procurement directives, namely the defence package, includes directives about intra-EU transfer directive, and the 2009/81 directive. Offset were part of it, even if not explicitly: a number of Communications by the European Commission state and clarify offsets are not allowed anymore. Offset in general means that somehow industrial collaboration has a return for society; and of course in Europe that is not allowed anymore, as the procurer is not allowed to offer it. But what we see around us is that industries, to ensure a local production, continue to use them if convinced it is necessary. Nowadays only few companies can afford to work in one market only and to sell they whole production there, because after all export is important both within the EU and at the world stage.

In order to carry out our project, we studied the defence package in depth. Despite it is supposed to work, we saw the new tools it introduces – i.e. certification – are not used really much. For example, representatives of small and medium enterprises we had the chance to talk with told us industries based in Western Europe did not know anything about them. An extensive use of the tools proposed by the Commission could create a better situational awareness about who does what and in which part of Europe. Do you agree?

We should not forget these tools are still in their early days of existence. From the day in which the idea was conceived – first thoughts came up to in 2004 – it took many years to put it in place – as far as I know 2010 was the deadline for the implementation, but there are still some member states lagging behind that date. Now it is fully implemented we have to wait and see how it develops, and I think the trend is difficult to see after only a couple of years. Next year there will be a first review of the Defence package to see how it has worked from the Commission side and how it can be modified and recast, and I think we have to wait for that analysis in order to better understand. On the other side, as you underlined, part of the integration effort has to come from the European Defence Agency; they had an internet based European bulletin board where tenders are published and where companies coming from all Europe bid in open competition. In fact, this has not really worked out: there were two European bulletin boards, one for industries – underlining opportunities of collaboration – and one for member states for public procurement. This should allow – as you mentioned – companies from certain part of Europe to know what is going on and take part of it. But at least for the time being it has not seemed to work out, so I think we need to put in place something else. In my opinion the 2016-2017 review would illustrate that. But it is also up to those defence industries associations and companies to push for it, to ensure they will have the opportunity to be involved.

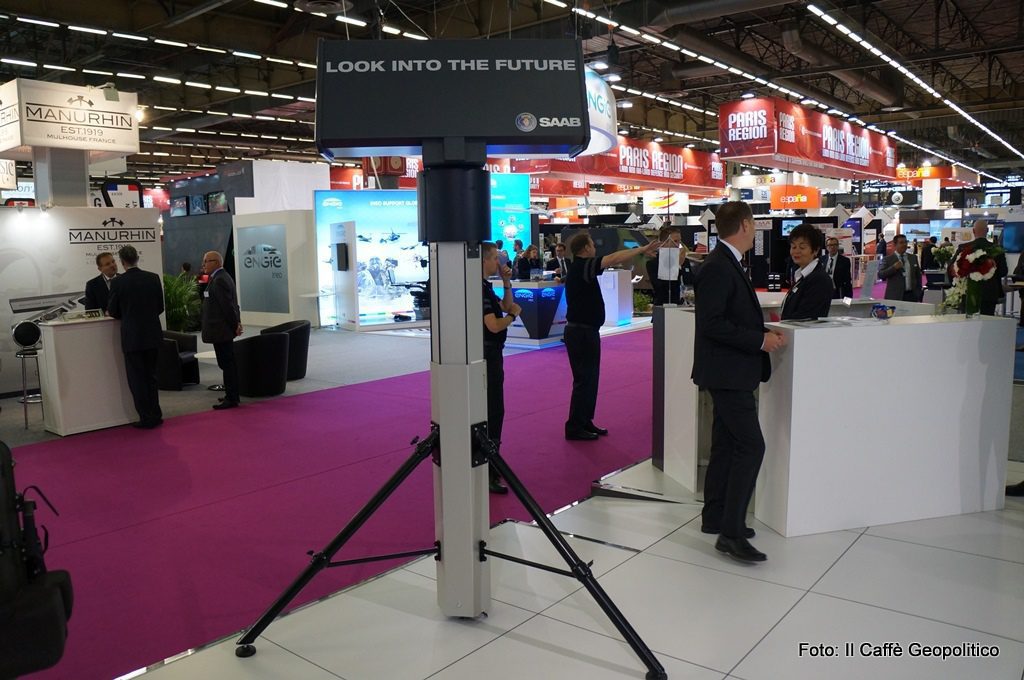

What products are you showcasing here at Eurosatory?

To answer this question, we had a guided tour of SAAB’s booth, having the chance to understand more about the products presented during the exhibition.

Starting from VSHORAD (very short-range) solutions, we discovered the mounted Giraffe 1X antenna and the RBS 70 NG missile launcher.

The Giraffe 1X antenna’s main strengths are light weight and flexibility. Weighting less than 200 kilos, it can be used by a single soldier and can be easily transported. It allows a high situational awareness on the battlefield, being able to detect a wide array of menaces, from asymmetric attacks to UAVs.

The system can be used in pairs with RBS 70 NG missile launcher, a 24/7 all target solution which proves particularly useful in the most challenging combat environments, as it is easy to use and to deploy and resilient to countermeasures.

SAAB’s support weapons were also showcased at the booth: the Roquette NG family (AT4CS ER, AT4CS AST, AT4CS HE), which will be delivered to France by 2017; the NLAW anti-tank weapon; and the Carl Gustav 4, the newest multipurpose, reloadable weapon system.

Simulating training model and CBRN solutions were also showcased at the booth, with a particular emphasis on the training system.[/one_half]

[one_half_last]Quanto e fino a che punto la geopolitica influenza le attività di SAAB?

Se intende i conflitti, per esempio, questi hanno un’influenza. Se scoppia un conflitto è necessario lavorare su ciò che deve essere usato, e questo vale per tutte le aziende.

Se la geopolitica è intesa in termini finanziari, economici e di budget per la difesa, questi sono aspetti che contano e che dobbiamo seguire e monitorare, così da assicurarci che le nostre risorse scarse siano allocate nel giusto mercato, e che questo abbia una rilevanza per noi.

Cosa può dirci delle compensazioni industriali? A quanto pare la loro importanza è in crescita, e la loro diffusione in aumento…

Le compensazioni sono una questione specifica. Come avrete notato nello sviluppo del vostro lavoro [il progetto analitico investigativo su cui stiamo lavorando – nda], la riforma introdotta con le direttive europee sul procurement, in particolare il defence package, comprende le direttive sui trasferimenti intra-europei e la direttiva 81/2009. Le compensazioni ne sono parte, anche se non esplicitamente: diverse Comunicazioni della Commissione europea sostengono e chiariscono che le compensazioni non sono più consentite. In generale, gli offset significano che in qualche modo la cooperazione industriale ha un ritorno sociale; e di certo in Europa questo non è più concesso, perché il produttore non può più offrirli. Quello che vediamo, però, è che le industrie, per assicurare una produzione locale, continuano a offrirli se li ritengono necessari. A oggi sono poche le aziende che possono permettersi di operare su un solo mercato e di vedere tutta la loro produzione lì, perché dopotutto le esportazioni, sia in Europa che all’estero, mantengono la loro importanza.

Ai fini del nostro progetto, abbiamo studiato a fondo il defence package. Nonostante sia considerato in funzione, abbiamo notato che gli strumenti introdotti – come le certificazioni – non sono usati estensivamente. Sfortunatamente, direi, perché credo li ritengo utili alla risoluzione di alcuni problemi. Per esempio, i rappresentanti delle piccole e medie imprese con cui abbiamo avuto occasione di confrontarci ci hanno detto che le industrie della difesa occidentali non li conoscevano. Un ampio uso di questi strumenti proposti dalla Commissione potrebbe consentire la creazione di una migliore situational awareness su chi fa cosa e in che parte dell’Unione. Lei concorda?

Non dobbiamo dimenticare che questi strumenti sono ancora relativamente nuovi. Dal giorno in cui l’idea è stata concepita – le prime idee in merito sono emerse nel 2004 – sono serviti diversi anni perché qualcosa si concretizzasse – a mia memoria la scadenza per l’implementazione era fissata al 2010, ma ci sono ancora Stati membri che la ritardano. Adesso che l’implementazione è totale dobbiamo aspettare e capire come questa si svilupperò, e credo che una simile tendenza non sia osservabile dopo pochi anni. Il prossimo anno ci sarà già la prima revisione del defence package, per vedere se, almeno sul versante Commissione, questo ha funzionato, e se sono necessari modifiche o rimaneggiamenti, e penso che bisognerà attendere questa analisi per avere una migliore comprensione. D’altro canto, come sottolineato, parte degli sforzi di integrazione devono venire dall’Agenzia europea per la difesa (EDA); loro hanno un bollettino europeo online in cui sono pubblicati i bandi e le aziende europee possono presentare le offerte in competizione aperta. Nei fatti, però, questo non ha funzionato: c’erano due Bulletin boards, uno per le aziende – sottolineando opportunità di collaborazione – e uno per il procurement pubblico degli Stati membri. Questo – come menzionato – può consentire alle aziende di alcuni Paesi europei di sapere cosa avviene e di parteciparvi. Ma almeno al momento questo non sembra funzionare, quindi credo serva dell’altro. A mio parere la revisione del 2016-2017 illustrerà tutto questo. Ma spetta anche alle associazioni di industrie della difesa di spingere per questi, per assicurare che avranno la possibilità di essere coinvolti.

Quali prodotti presentate qui a Eurosatory?

In modo inedito, per rispondere a questa domanda abbiamo fatto una visita guidata dello stand SAAB, potendo così comprendere meglio i prodotti presentati al salone.

Partendo dalle soluzioni VSHORAD (cortissimo raggio), abbiamo scoperto l’antenna montabile Giraffe 1X e il sistema missilistico RBS 70 NG.

Il punto di forza dell’antenna Giraffe 1X sono leggerezza e flessibilità. Pesando meno di 200 chili, può essere usata da un unico soldato e può essere trasportata facilmente. Consente di ottenere un’ampia situational awareness del campo di battaglia data l’abilità di rilevare un’ampia gamma di minacce, dagli attacchi asimmetrici agli aeromobili a pilotaggio remoto.

Il sistema può essere usato in coppia con il sistema RBS 70 NG, una soluzione operabile h24, 7 giorni su 7, che risulta particolarmente utile negli scenari più impegnativi, perché è semplice da utilizzare e resistente alle contromisure.

Allo stand era anche presente l’armamento di supporto prodotto dall’azienda finlandese: gli ordigni controcarro della famiglia NG (AT4CS ER, AT4CS AST, AT4CS HE), che saranno consegnati alla Francia entro il 2017; l’arma anti-carro NLAW; e il più recente, multiruolo e ricaricabile sistema d’arma Carl Gustav 4.

Tra le altre soluzioni esposte, un modello di simulazione di addestramento (sul quale è stata posta particolare enfasi) e soluzioni CBRN.[/one_half_last]

The interview ends here. We warmly thank Henrik Vassallo and SAAB for their kind cooperation!

Giulia Tilenni

[box type=”shadow” align=”” class=”” width=””]Un chicco in più

SAAB is the leading Swedish company in the defence sector. SAAB operates in every continent, being also a relevant company at the global level. In order to maintain its key role, the company reinvests 20% of its annual sales in research of new systems.

SAAB è l’azienda svedese leader nel settore della difesa. Opearante su tutti i continenti, SAAB è ormai un’azienda chiave a livello mondiale. Per poter mantenere il proprio ruolo, il 20% dei proventi delle vendite annuali è reinvestito nella ricerca di nuovi sistemi.

Per chi volesse approfondire, questa intervista è parte integrante dello speciale che Il Caffè Geopolitico ha dedicato al salone Eurosatory 2016. [/box]